Dorothy Downs: on story, film, and collaboration

followed by a conversation with Rev. Houston R. Cypress

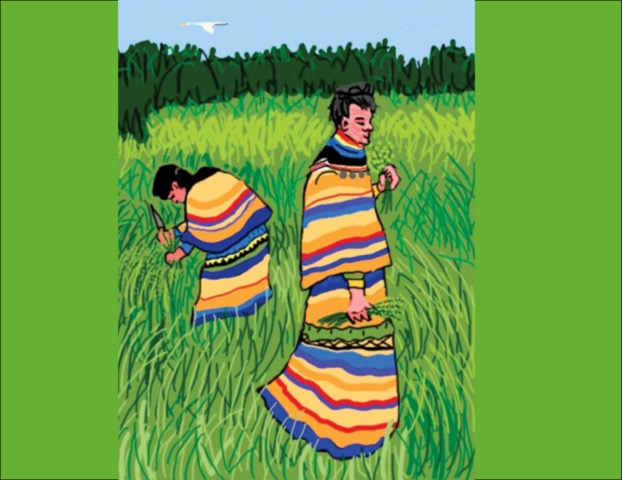

The people learned how to live and care for nature, the trees and plants, the clean water, and all that inhabited the river of grass. They were told what they should grow or hunt to eat. This story tells how the family lived then and honored Breathmaker at the annual Green Corn Dance.

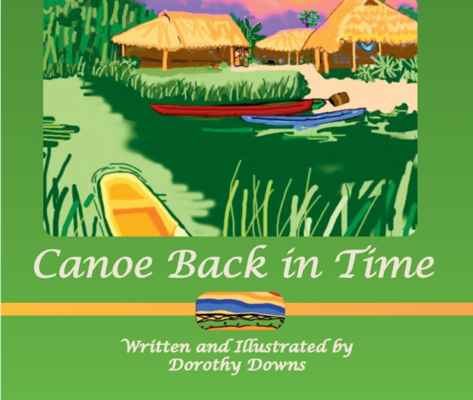

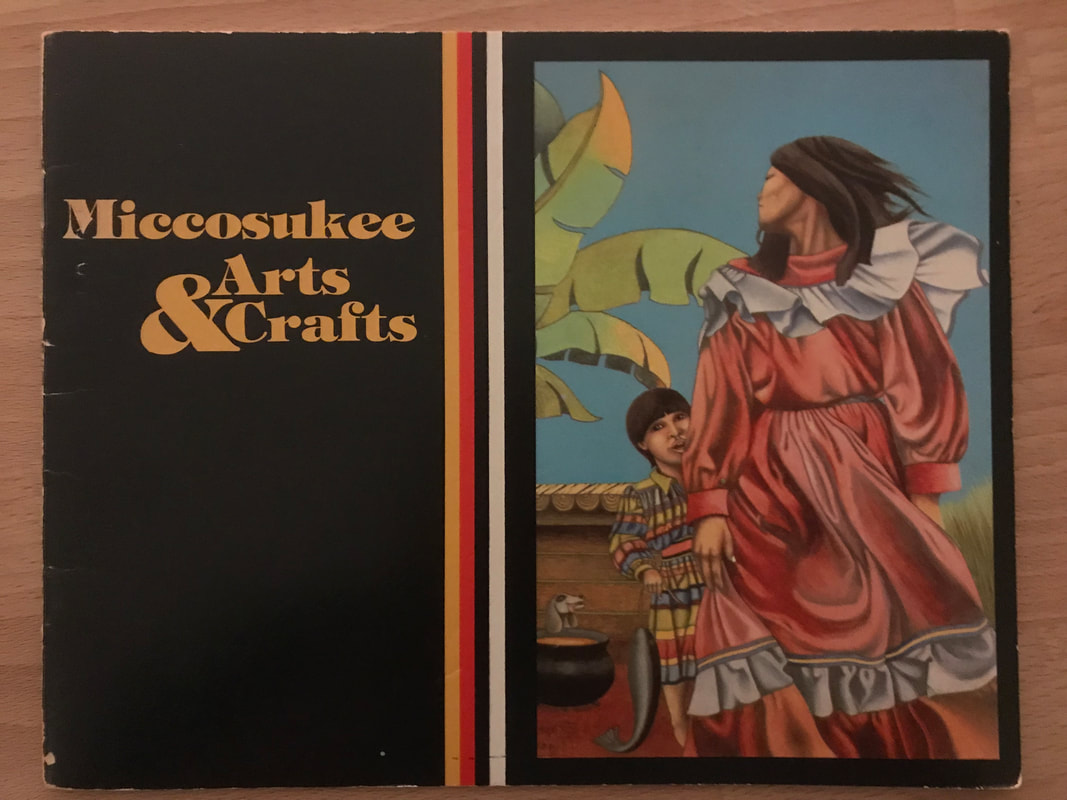

Miccosukee founding Chairman, Buffalo Tiger, told me stories and said he wanted a book written for children, telling them the family values he was taught. He asked me to write Miccosukee Arts and Crafts, published by the tribe in 1982. I have written and illustrated this book for him and the Miccosukee people. Canoe is a work of fiction, strongly based on real stories told to me and on real people with my mixture of first and last Miccosukee names and clans. I thank everybody.

In the early 1920s, the Miccosukees were worried about what effect the building of the road across the Everglades to be known as the Tamiami Trail would have. I have included in Canoe a story of an event at Green Corn Dance, during a time when the men talked about business:

As an art historian, I have written about all of the arts of Miccosukees and Seminoles. Once a creative girl and artist myself, my special interest is tracing the history of patchwork clothing and the women artists who sew it. Sally Osceola's excitement about creating art is the spark for the storyline.

I hope the reader enjoys the trip back to the beautiful Everglades we Love.

❤🙏

(Published by IRIE Books, Santa Fe, NM. Available on amazon.com.)

We had just finished re-watching Patterns Of Power, an hour-length feature produced by Dorothy on Miccosukee & Seminole patchwork, and the community that created this unique sewing technique in the Everglades. It’s captivating to listen to the music inherent in the cadence of the Miccosukee women, firmly situated in the various institutions of a tribal community after 2-and-a-half decades of federal recognition and self-determination: Delores Billie and Virginia Poole in the Miccosukee Health Department, Jennie O. Billie in the Miccosukee Indian School.

Dorothy Downs contributed to the momentum of Miccosukee artist Stephen Tiger’s art career by giving him his first one-man exhibition at her Four Corners Gallery in Coral Gables. Stephen, and his brother Lee, are the nexus of the Miccosukee rock-&-roll band TIGER TIGER – they brought a psychedelic indigenous force to the stage in their day. Today there are other Miccosukee music bands like TALKING DOGS, but TIGER TIGER blazed the path. These guys, along with their father, Hon. Buffalo Tiger, started the annual Miccosukee Arts Festival, which celebrates indigenous culture in the Everglades for one week after Christmas.

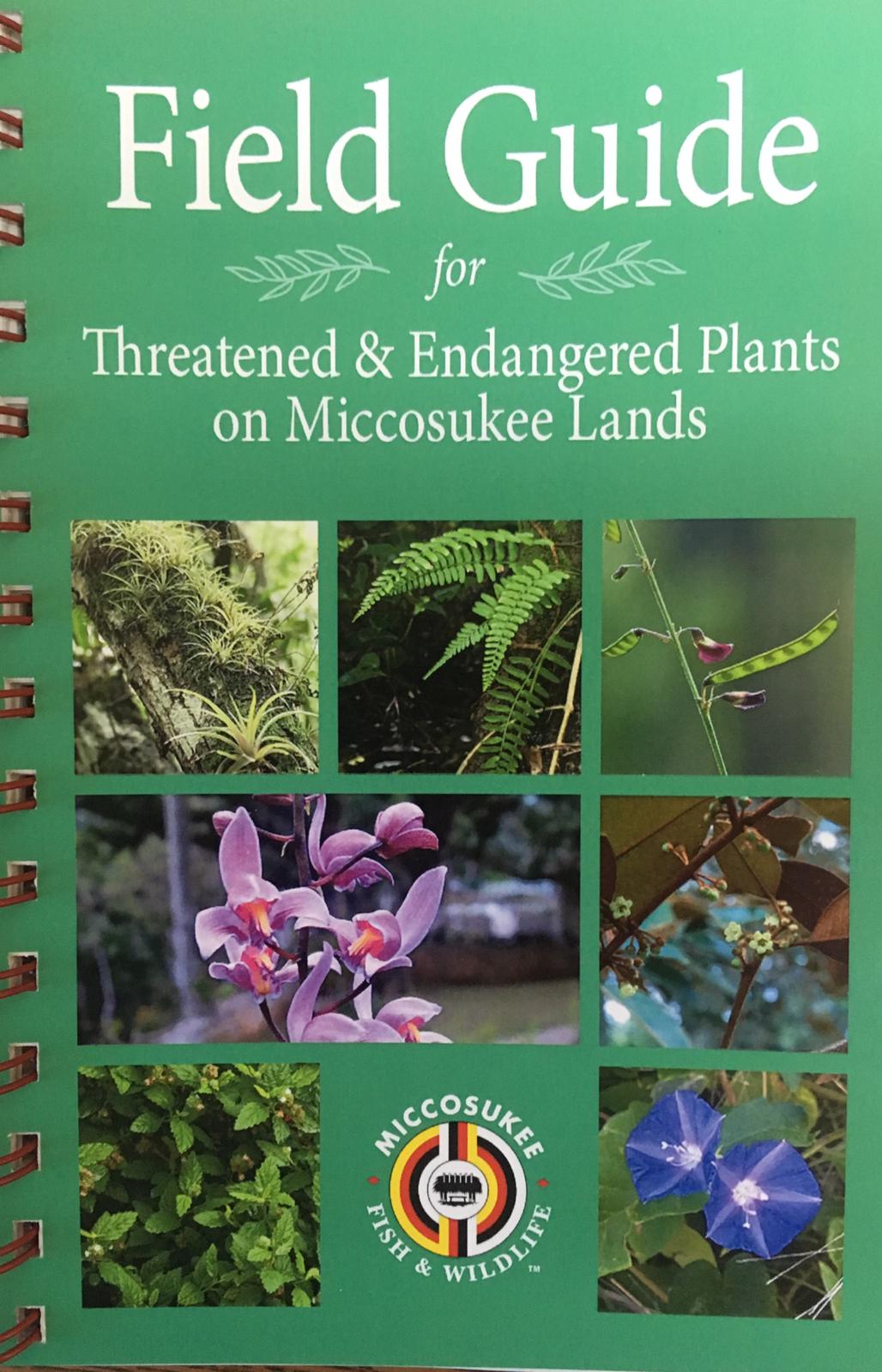

Times have changed for the Miccosukee Tribe these days. The newest Miccosukee publication comes from their Fish & Wildlife Department:

With important film events featuring indigenous stories coming this fall with Borscht in Miami, & at FGCU in Naples, exploring Dorothy’s newest work underscores the importance of creative solidarity between communities, and the enduring sexiness of cinema.

I’ve had the pleasure of getting reacquainted with your work over the past couple of years. I deeply appreciate how you always show us love when we setup at different tribal festivals. I love how the land and the Everglades shows up in so much of what you’ve produced in collaborating with the indigenous communities. Let’s talk about you as a writer.

D:

At first I didn’t think I was literary. But I guess I’m a writer HAH! look at all this. (Gestures to her books.). The 1981 Miami Herald Tropic Magazine article, "Chickee Chic." It’s a nice big article. I went to a high school reunion and a girl in my class happened to be an editor at Tropic. "She said what are you doing now?" I said," Oh well, I just finished my Masters Degree at UM in art history and I’m doing a little writing.“ She said, “Well write something for me.” She called me in to The Miami Herald, and there was this room with a glass window. There were people waiting, and I went in and she asked me questions. She said, “There’s a typewriter, now go write it.” I didn’t even type! Much later, a friend told me, “I can’t believe what you wrote in the paper about Marjory Stoneman Douglas!”

H:

What has it been like learning from and learning with communities?

D:

I am so dependent on that and so fortunate the people would share with me so openly. You saw in the video how Frances Osceola and all these people are happy to be able to share. So I feel so fortunate that they are that open to me and I started this in 1976, a long time ago. I didn’t bring gifts. I’d just go in, sit down, say Hi, and start talking. And they would just work. Frances with Wild Bill. Effie didn’t speak English, so Howard was there. These people opened up to me and maybe they saw the importance of it, too. The first person I interviewed was Howard Osceola, and I said, “Do you mind if I tape you?” He said, “Oh no I tape my father-in-law all the time, Josie Billie.” So I learned it was okay to tape, because they wanted this information saved, and I saw that I could help them do that. I met Howard through the University of Miami, because he was working with Iron Arrow, the Honor Society at UM.

H:

How has producing the film changed you since then? Or how has it impacted you?

D:

When I would go out to interview people, I would leave the City of Miami and drive Tamiami Trail and suddenly things would change. Suddenly you’re in the Everglades. And I may have had some ideas and questions in my head, but I would get out there and let the people tell me what they wanted to say. But just the environment of being out there, listening to them talk about what they love and do, but then coming back, just remembering what they said, not what I wanted to know. And the beauty of the Everglades changed the whole thing. Just going into it, experiencing it, and then coming back. That was really important to my work. I’d like to say how much I appreciate having this as a lifetime goal. I feel so lucky to be able to do what I do and be accepted for it.

H:

What do you mean? Tell me more.

D:

I believe that my mission in life is explaining the beauty of cultural diversity through art. That is what I somehow recognize. I feel chosen for that. I don’t know why. It’s just something I started doing and the path went on and on. I met people. I met Miccosukee people. I feel like that’s what I’m here for. And yes it not only deepens me but it’s what I’m supposed to do. Now I don’t want to sound strange about that, but, you know, sometimes you feel this is just right.

H:

You’ve had experience working with other indigenous communities, and I feel that my concerns are how traditional concerns and ecological concerns come together. Do you have any experience with that in your relationships with other indigenous communities?

D:

I’m a Miami girl. I was born in Miami and I so feel a love for the Everglades, for the whole thing, for the ocean, for the bay. It’s very easy to be supportive of the Everglades. The other communities I’ve worked with – say Navajo, or Pueblo potters – they’re different from here. This is where I’m from, and to me that is really important, to tell the story of where I was born.

H:

Well, around here these days, in the circles I visit, people are concerned about the Environment, Climate Change, and Justice. What’s the role of Art in this context?

D:

Making people stop and look and think. Art is a way to introduce people. This is the Everglades, this is how beautiful it is, and we need to take care of that. Protect it. And I think it can be done visually, more than any other way. Or as equally as writing about it. But visually you see the beauty of it. That makes people stop and think, “Wait this is important, we can’t let go of this.” And that’s the role art plays.

[email protected]

Her book can be ordered on Amazon.com

Upcoming Events will be at FGCU, and at the Borscht Corp, during November 2019.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed